Abstract

Inspired by my participation in the seminar Applied Neuroscience led by Jim Hickman for Ubiquity University, this paper is centered on exploring the intersection between the fields of neuroscience and self-development or inner work.

After clearing some preliminary concerns, the paper will examine some of the ways in which neuroscience can support the understanding of the human journey. Specifically, I will focus on the concept of embodiment, explaining its relevance for inner work and its connection to the latest neuroscientific studies. I will also present some practices that support embodiment, inspired both by the seminar and my own personal experience.

The paper will then investigate some of the possible ethical questions that arise from the frameworks and practices presented, and conclude by proposing that the mutual influence between neuroscience and inner work allows both fields to flourish in a more complete, harmonious, and grounded way.

Context and Concerns

There is no doubt that the brain is one of the most fascinating things there are. Who would not want to know more about it? And yet, in approaching a course on neuroscience, I could feel some concerns. I come from an academic background in philosophy, and I have dedicated a good portion of my life to spiritual study and practice. For years, I have been focusing on the phenomenology of consciousness and its artifacts, rather than studying the brain as the ostensible physical seat of consciousness. I have come to the conclusion that the inner world is just as vast, mysterious, and incommensurable as the Universe; exploring the phenomenology of consciousness means venturing into an infinite field that we can experience, yet never completely understand. As a consequence of my approach, I have little faith in any form of reductionism1 when it comes to our inner world. I do not think, or hope, that we will ever be able to explain the contents of consciousness in neurological terms, any more than we will ever be able to explain the beauty of a work of art in terms of the chemical composition of its pigments. I am therefore concerned with any scientific attempt to reduce thoughts, feelings, beliefs, and other phenomenological entities of our inner world to neural patterns, hormones, and brain components.

Fortunately, many scientists and researchers from the field of neuroscience see consciousness not as something that can be explained away, but as a mystery to behold with awe and respect. There is a whole field at the crossroads between neuroscience and inner work2, and this field is fertile. There, in this intersection where science dares to be mystical and inner work dares to be scientific, neuroscience can contribute its important insights to a holistic view of the human experience. In return, neuroscience benefits from being exposed to inner work: a more holistic approach puts neuroscience into a context, embeds it in the vaster enterprise of understanding human life, and protects it from the danger of becoming a reductionist, dispassionate examination.

In Jim Hickman’s seminar Applied Neuroscience, we approached the brain (and the whole nervous system) from this hybrid angle. We recognized the brain as a hyper-complex system with significant emergent properties. Hypercomplex systems are those whose behavior we cannot easily predict based on our current information; oftentimes, this is because our very observation of the system influences its state. One of the fundamental properties of hypercomplex systems is emergence: the system exhibits properties that cannot be inferred by simply examining its components. A mechanical engine, for instance, is not a hyper-complex system, and emergence does not play a significant role in it: we can understand the engine by decomposing it into parts and studying their individual behavior.

But if we study the brain as if it were a mechanical system, we are inevitably drawn into a reductionist dead alley. By acknowledging the hyper-complexity of the brain, we can still investigate the functioning of its parts, yet we maintain a sense of awe and respect for this most mysterious organ. In this way, science can tap into what, in spiritual traditions, has been often called “the mystery”—the ineffable quality of is-ness of a reality that both invites and eludes our attempts at making sense of it. In this sacred awe, in this willingness to approach the study of a phenomenon that we might never fully explain, I see not a limitation, but a safeguard against the danger of overinflation of the intellect, a guarantee that our endeavor to explore the functioning of the brain will be aligned with the overarching goal of evolution of our human consciousness.

Science has already brought us to the limits of our capacity to make sense of the reality around us, through the development of quantum physics and the theory of general relativity. Human consciousness is the other edge frontier of our capacity to understand. When studying consciousness, we are flirting with the incomprehensible and the paradoxical. Our endeavor to study our own consciousness resembles the impossible yet mesmerizing feat of a mirror trying to reflect itself, a camera trying to take a picture of its own lens. The paradoxical nature of this enterprise, however, is not problematic, as long as we are willing to open our minds to the mystery and humble our intellect before the limits of our capacity to know.

With these concerns named and with some context for our exploration, I will dedicate the rest of the paper to investigating the field of possibilities where science and inner work influence, challenge, and enrich one another.

The Brain as a Gateway

In some ways, the encounter between neuroscience and inner work is a direct consequence of the nature of the brain as a gateway between the physical and psychic world, and between inner and outer reality. The more neuroscientific studies progress, the more we discover ways in which stimulating different parts of the brain can shape and alter our inner experience, that is, different ways in which the physical level affects the psychic level, the outer world the inner. But as it turns out, the opposite is also true: thoughts and emotions can influence our physical reality, re-shaping our brain. The psychic can affect the physical.

The concept that through the power of thought we can change our material conditions is not new. Mystical traditions have always expressed the idea that through thought infused with emotion, we can influence matter in profound ways: in a sense, this is one definition of prayer. But in the last century, the interrelationship between mind and matter has started to be acknowledged outside of the so-called spiritual circles. In 1937, Napoleon Hill published Think and Grow Rich, in some ways the grandfather of all contemporary books on the manifesting power of thought (Hill, 1960). Hill posited that by the power of thought married with emotion, one can accomplish great feats, and create fortunes. Hill’s main preoccupation was how to make millions of dollars—he saw that as the ultimate test of human value and genius. We do not need to agree with Hill’s markedly capitalistic view to recognize that he was pointing to the age-old idea that the inner world can influence the outer world. Although Hill’s study was not supported by scientific evidence, many of his tenets have been indirectly confirmed by the latest findings in both neuroscience and inner work. In this sense, Hill anticipated the findings of modern authors, some of which we will explore in this paper, on how thoughts and emotions can shape our brains and affect our lives.

In Buddha’s Brain, Rick Hanson (2009) makes the case that by knowing how our brain works, we can improve our lives and be happier, kinder, and healthier. To that purpose, Hanson gives us a neurological understanding of why we suffer. Part of the reason for human suffering is the neurological mechanism known as “negativity bias” (Hanson, 2009, p. 42): for evolutionary reasons, our brain has evolved to pay particular attention and dedicate specific storage space to negative or threatening experiences. It makes sense: those of us who remembered that a stick-shaped object lying on the ground at night could be a poisonous snake, and therefore avoided it, had better chances of survival than those of us who did not—even if the object was a harmless tree branch after all. The trouble is, this evolutionary trait of the brain is not adapted to the conditions many of us live in today, when actual survival threats are replaced by low-intensity (and more or less constant) stress. Today, according to Hanson (2009), we are grappling with the consequences of having a brain built to be “Velcro for negative experiences and Teflon for positive ones” (p. 41).

Aside from having a brain evolutionarily wired to give more specific weight to negative than positive experiences, we humans are also meaning-making machines. We not only retain negative events, but anticipate future negative outcomes and, over time, we build stories around our experiences. In other words, we are the only animals that “suffer that we suffer” (Hanson, 2009, p. 12). We suffer not only because of “first darts” (unavoidable physical or mental discomfort) but also because of “second darts”: the meaning we assign to our painful experiences (Hanson, 2009, p. 50). In today’s world, mild to severe post-traumatic symptoms do not need to be associated with events like war, famine, or sexual abuse: they can be triggered by negative events as varied as stress at work, relationship issues, and many more conditions of modern life. It is almost as if the negativity bias of the more ancient survival-driven structures of the brain, in combination with our advanced capacity to anticipate future outcomes and remember past events, created the ideal conditions for long-lasting and pernicious trauma caused even by situations that are anything but life-threatening. We are sensitive animals living in a world that is increasingly different from that in which our brain evolved, and whose primal instincts are often maladapted to the reality that surrounds us.

But our brain’s capacity to simulate situations and trick itself into believing they are real (Hanson, 2009, p. 43) is also a blessing in disguise, for it is upon this very ability that most systems of self-healing through the power of thought are based. Well-known inner work teachers like Tony Robbins, while lacking a rigorous scientific formation, have used their intuitive knowledge of how the brain works to create systems of inner work that are, apparently, highly effective. In Awakening Your Inner Giant, Robbins (2007) acknowledges that “with enough emotional intensity and repetition, our nervous systems experience something as real, even if it hasn’t occurred yet,” and proceeds to teach us how to “use imagined references to propel us in the direction of our dreams” (p. 80). This is, in a nutshell, the same thesis Hill exposed in the thirties, only now backed by more scientific awareness of how the brain works.

Even though he may not use the term, Robbins is also aware of negativity bias and has an idea of how to use it to our advantage. According to Robbins, all personal improvement starts with a change of belief, but beliefs are stubborn and hard to change. So how do we change them? By using negativity bias to our advantage, says Robbins (2007), and inducing our brain to “associate massive pain to the old belief” (p. 91). While Robbins’ insights about how the brain works may not always be scientifically precise, if we had to judge by the enormous success of his programs, it seems that his system does produce results. If thousands of people feel better and change their behavior after following some of Robbins’ techniques, the question of whether they are based on accurate scientific modeling of the brain may seem to lose some relevance—at least from the standpoint of applied neuroscience.

But perhaps the most daring proposition at the crossroads between neuroscience and inner work is that the state of our brain directly affects our health and that, therefore, by changing our thoughts and beliefs, we can cure illnesses. Joe Dispenza is one of the most well-known proponents of the idea that we can use thought to literally change our body’s physiological state, and he often uses neuroscience-inspired concepts to back his teachings. In You Are The Placebo, Dispenza (2014) argues that through the use of intentional thought reinforced by strong emotions, we can “trick” our body into generating a state of health even in the face of conditions like Hashimoto’s disease or multiple sclerosis (pp. 199-232). The subtitle of Dispenza (2014)—“making your mind matter”—is a well-thought wordplay on one of the metaphysical foundations upon which his work is based: the idea that thought can influence physical reality. Dispenza (2014)’s metaphysical explanations of how exactly this happens range from plausible (matter is energy at its slower vibration rates, p. 186) to frankly confusing (health equals “coherence” of vibration among the different cells of our organism, and higher frequency equals more coherence, pp. 193-195). As expected, Dispenza’s ideas and methodologies have been questioned by the scientific community; yet, his events continue to attract thousands of people and, if we trust his own accounts of the healing process that some participants experience, to change many people’s lives.

These are just particularly well-known examples of the intersection between neuroscience and inner work, a field that is still in development, and that may never be as rigorous as a purely scientific study of the nervous system. Yet, the capacity of teachers like Hanson, Robbins, or Dispenza to affect our culture and society is indisputable. Whatever our opinion about their methodologies, it seems clear that knowledge of the brain and the nervous system can indeed contribute significantly to our happiness and health, and support our journey of self-knowledge. Having worked in the field of inner work for more than fifteen years, I can testify that neuroscience has a growing role in supporting the transformational work of individuals and groups. Hanson (2009) is extensive in describing how neuroscientific concepts can support the practice of meditation and mindfulness (pp. 177-190). But there is another aspect of inner work where neuroscience is offering a fundamental and growing contribution: the anchoring of consciousness into the body. Here, neuroscience can be key in addressing one of the most actual and pressing needs in any form of inner work: that of understanding our inner experience as an interaction between mind, feelings, and body. Neuroscience, when free from reductionist drifts, can be a precious ally in our journey of rediscovery of embodiment.

Back to the Body

We live in a largely disembodied world, and we have been for centuries. To understand that, it is helpful to zoom out and look at the evolution of human consciousness over the last millennia. Using the model proposed by Anne Baring (2013) in The Dream of the Cosmos,we are living at the end of what Baring calls the “solar era,” a chapter of our collective history that has lasted for roughly four thousand years. During the solar era, human consciousness has gained an astounding degree of refinement and complexity, but at the price of severing the connection with the instincts, the emotions, and the body (Baring, 2013, pp. 393-395). As a result, one of the main characteristics of the solar era is a marked process of disembodiment.

Today, we are so immersed in a disembodied culture that it may be hard to even notice, and disembodiment is ever more pronounced as we go up the social and economic ladder. Most decisions that influence the world on a global scale are taken by leaders that are (or pretend to be) utterly disconnected from their own body. Try to imagine what would be the public opinion’s reaction if one of those world leaders, while making a solemn announcement, stretched, yawned, and did some squats to relieve the discomfort of their body. We attribute credibility to people in power, as well as scientists and scholars, based on how stiff they are, how disconnected from their body they look, how much of a “talking head” they seem to be. This is based on a characteristic tenet of the solar era: that the body is both antagonistic and inferior to our rational mind—the one aspect of our human totality that, during the solar era, rose to almost undiscussed dominance (Baring, 2013, p. 126).

While the phenomenon of disembodiment has long been discussed by philosophers and spiritual teachers, it is refreshing to see it addressed by neuroscientists. In The Master and His Emissary,Iain McGilchrist (2019) offers a neurological take on the problem of disembodiment as one of the consequences of the dominance of the left hemisphere of the brain over the right. McGilchrist’s view is that the two hemispheres operate on alternative and, to some extent, incompatible world-views. While the left hemisphere sees itself as separate from a world that it can manipulate and describe symbolically, the right perceives itself as part of an organic world that it feels and responds to. Therefore, only the right hemisphere is “embodied,” and in fact, only the right hemisphere is capable of perceiving the body in its entirety; the left hemisphere only sees the right half of the body, the one that it controls (McGilchrist, 2019, p. 66). In a sense the left hemisphere, according to McGilchrist, is our reductionistic brain, while the right one is our holistic brain: the left hemisphere has a tendency to see the body as an assemblage of parts, a tendency, it should be noted, that has dominated in scientific circles until very recently (2019, p. 439).

While both hemispheres are important, according to McGilchrist (2019) the right hemisphere (the “master”) is the one that provides both the grounding and the ultimate integration of our perception of the world (p. 46). The left hemisphere (the “emissary”) is a wonderful servant, whose rightful job would be to support the work of the right hemisphere in a utilitarian fashion, and hand over control back to the right hemisphere once its job is complete.3 However, the left hemisphere has a tendency to forget about its role, and to believe in its own world-view as complete and definitive. As a result, it usurps the master’s throne, creating a false perception of reality and the body as separate from the perceiving consciousness (McGilchrist, 2019, pp. 428-462).

In the context of Western thought, it is Descartes, the 17th-century philosopher and mathematician, widely considered as one of the founders of modern philosophy, who has the dubious honor of representing the epitome of left-hemisphere dominance. Descartes’ famous cogito, ergo sum (I think, therefore I am) is in a sense the motto of disembodiment and, in McGilchrist’s view, the expression of someone whose left hemisphere is in full control (2019, p. 332). In Descartes’ meditations, the existence of a disembodied consciousness becomes a metaphysical conclusion, the result of his methodological choice of rejecting anything that can be doubted by the mind. Feelings, sensations, the existence of one’s own body is discarded as potentially illusory, but the organ doing the discrimination is the rational mind, taken as the ultimate judge of truth and, therefore, of existence. There is no denying that Descartes’ inner research, the quest of a mind that, alone, sets forth to discover the ultimate truths about life, is a bold experiment. And yet, as McGilchrist (2019) points out, Descartes is also dangerously disconnected from reality: he literally doubted that he had a body at all (p. 333). The state of disembodiment that Descartes experienced is, in fact, remarkably similar to the situation of some people affected by schizophrenia, to whom their own body can feel illusory, unreal, or similar to a mechanical device (McGilchrist, 2019, p. 335).

Before we dismiss Descartes’ meditations as the symptom of the excesses of Western rationality, it is important to realize that his disembodied view of consciousness is not all that distant from the positions of some of the most revered Eastern spiritual traditions. Buddhism, for instance, is at its core also founded on the primacy of reason, and on mistrust of the senses and the body. The traditional Buddhist antidote to life’s suffering is given by way of a relentless rational dissection of the human experience. For example, in the Bodhicharyāvatāra, one of the foundational texts of Mahayana Buddhism, the Buddhist sage Shantideva expresses wariness and contempt for the body, which he considers as nothing more but a sack of filth (Shantideva, 2008, pp. 195-196). The objective of Mahayana, according to Shantideva, is the development of bodhicitta, the awakened mind; from it, compassion arises naturally. But in order to attain bodhicitta, the mind has to realize that it is fully separate from the body, and stop acting as if the mind and the body were united (Shantideva, 2008, p. 115). If Descartes’ position echoed the schizophrenic’s pathological disconnection from the body, which he sees as an inanimate object, Shantideva is not far behind when he reasons that, since we enjoy touching or beholding the skin of a loved one, we should equally desire to touch a piece of skin or human flesh “inanimate and in its natural state” (2008, p. 195).

I make these observations about the disembodied nature of mainstream Buddhism not to undervalue the historical need of disengaging consciousness from the bodily processes (which is one of the defining characteristics of the solar era), but rather to point out how that need was nearly universal across both East and West. There are, of course, exceptions; some mystical and philosophical traditions, like Buddhist and Hindu Tantra, have struggled hard to keep consciousness anchored to the body. And yet, barring those notable exceptions, we have lived for centuries in a culture traversed by the drive to use the mind to abstract from, analyze, and ultimately dominate the body and nature. Given this general tendency towards abstraction and disembodiment, it comes as a relief that science today is becoming an ally in reestablishing a more balanced, harmonious relationship between mind and body. Neuroscience-based insights are proving, time and again, how our consciousness is inextricably connected and grounded in a physical layer.

Neuroscience has significantly improved our comprehension of how people act and feel when undergoing intense experiences. By understanding the different components of our brain, their different evolutionary function, and their complex and often contradictory relationship with each other, we can better make sense of our sometimes paradoxical response to both inner and outer events. As Hanson (2009) pictorially says, our brain is a “kind of a lizard-squirrel-monkey brain” (p. 24): the assemblage, shaped by evolutionary forces, of various interrelated components each of which may or may not act in synergy with the others. Our existence has only fairly recently evolved out of a reality where, quite literally, our life was at risk every day, and the deepest, most ancient structures in our brain are still wired for survival. For this reason, we can and do often react to experiences that are anything but life-threatening with reflexes that would be more adapted to life in the jungle. Understanding our psychological survival mechanisms has become an increasingly necessary aspect of inner work, a path that, by its very nature, requires us to go out of our comfort zone, experiencing challenging and sometimes confronting situations.

Until the information coming from neuroscience started to enter the field of inner work, the latter was jeopardized by a specific form of bypass. Failing to acknowledge the deep mechanisms that move the more ancient parts of our nervous system, many inner work circles were treating humans as purely conscious agents, sometimes with disastrous results. For instance, when doing inner work in a group, people can be confronted with traumatic memories, which in some cases may lead them to experience a state of nervous system arousal as if their life was under immediate danger. On a neurological level, parts of the “squirrel” brain (the so-called limbic complex) like the amygdala get activated much in the same way as if a predator was pouncing towards us at full speed. When this happens, for someone to calm down and analyze the situation rationally—activities that require the cooperation of advanced brain components like the pre-frontal cortex (PFC) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), both relatively recent parts of our “monkey” brain—can be almost a neurological impossibility. When the amygdala is flared up, and our bloodstream inundated with threat-response hormones, the relative strength of both the PFC and the ACC is diminished, so that some people literally “cannot think straight” when under the effects of the action of the limbic system (Hanson, 2009, pp. 51-53). In these cases, an embodied approach works much better: instead of asking the person to analyze their state cognitively, we can guide them through simple practices that promote direct contact with the body and its sensations, such as the practices I will share below. The person then starts to feel safer, realizing that the signals coming from the senses do not point to any immediate danger; they slowly begin engaging their cognitive capacities, and eventually can make better sense of what is going on.

What are then some ways in which we can support our consciousness in coming back to the body? Thanks to increasing awareness of the embodied nature of our consciousness, we can devise and access practices that, by soothing and energizing different parts of our nervous system, support us in staying connected to the body. My observation is that the different techniques that promote embodiment fall into three broad categories: physical techniques, breathing techniques, and awareness techniques. Let us see some examples of embodiment practices from each of these categories.

Embodied Practices

Unsurprisingly, one of the best ways of promoting embodiment is by moving the body itself, while staying present and conscious. Something as simple as stretching is one of the ways that we can bring the nervous system back to a state of equilibrium. Unfortunately, as noted before, there are strong collective biases against doing precisely the kind of movement that our body needs. It is difficult to promote a culture of embodiment if we are not ready to let go of the prejudice that the physical expression of credibility is a stiff physical posture.

Another simple and effective embodiment technique is shaking the whole body. Shaking helps release stress and brings our awareness back into the body from whatever anticipation of the future or recollection of the past it may be immersed in. Shaking also helps with our emotional states: while, at times, it may be important to do some introspection and investigate the emotions that are populating our inner world, in some cases we feel an indistinct emotional charge that simply needs to be moved so that we can go on with our lives. In those situations, after shaking the body for a couple of minutes, we generally feel more relaxed and more current—able to meet whatever inner and outer conditions are present in the moment with a nervous system that is more energized and available.

The next category of embodiment practices is the vast realm of breathing techniques. When our awareness is disconnected from our body, our breathing usually becomes shallow, irregular, or stuck. Bringing attention back to the breath is an almost infallible way to start bringing awareness back into the body. Focusing on the breath has the advantage of anchoring our awareness in a process that has both a physical aspect—the alternating movement of the diaphragm—and a mental aspect, given that it is possible to breathe voluntarily. In this respect, breathing is unique among other bodily functions: it is normally an automatic process, regulated mainly by the brainstem, but unlike other automatic processes, like digestion or cardiovascular function, we can take voluntary control of it. In this way, breath is one of the natural gateways between body and mind.

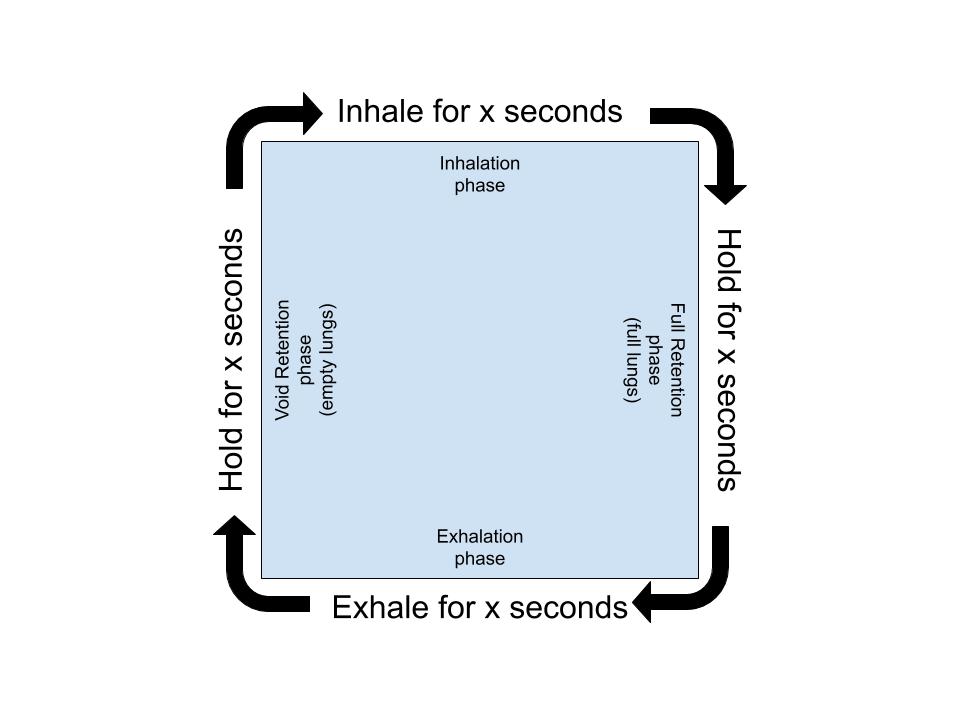

Even just a series of long, deep inhalations, each followed by a relaxed exhalation with a sigh, is an effective way to get back into the body. But for those that wish to explore the science of breathing more in-depth, both the Indian Yogic tradition and the Chinese Daoist tradition have accumulated centuries of wisdom about how to regulate the breathing to affect our body and consciousness. In Hatha and Kundalini Yoga, the traditions that I have studied, breathing techniques are called pranayama. Among the many pranayama techniques, one of the most valuable for embodiment is the “equal pranayama” (Sanskrit: samavritti pranayama): the practitioner follows a pattern of equal duration for the phases of inhalation, full retention (pause at the end of the inhalation), exhalation, and void retention (pause at the end of the exhalation) (see Figure 1). Thus, for instance, one inhales to the count of five4, rests with full lungs to the count of five, exhales to the count of five, and rests with empty lungs, again to the count of five. With practice, the count can be increased, but always maintaining the equal proportion among the four phases. The equal pranayama is among the most effective for grounding our consciousness when we feel scattered and disconnected from our body.

Finally, we can achieve embodiment by means of awareness techniques, without the support of any specific physical movement or breathing pattern, although that will usually require a certain degree of mastery. One of the simplest such techniques is the “body scan”: moving our awareness, in a controlled and progressive way, through all the parts of our body. I have found that the best way to do a body scan is bottom-up, starting with the toes and making my way up to the top of the head; in my experience, the simple act of bringing awareness to a part of the body both relaxes it and energizes it. This is in line with the ancient maxim that “energy follows thought”: by simply placing our awareness in one part of the body, we inundate that part with energy which, in turn, allows the part to relax and bathe in a nutritional field. Becoming aware of physical contraction is, in most cases, sufficient to produce some relaxation: contraction in the body starts to dissolve once it is made conscious. Aside from the relaxing and energizing effects, the body scan is also a great practice to train our capacity to sustain awareness.

Practices such as shaking, breathing intentionally, or scanning our body are simple actions that can become ingrained in our everyday life with relative ease. Including those and other embodied practices in our everyday behavior may be one of the shifts of paradigm that we most need. What would our society look like if we saw shaking, breathing deeply and sighing as perfectly natural? If we want to recover our embodied nature, then we need to get used to teachers, students, politicians, doctors, businessmen and businesswomen being embodied creatures. We need to question our association of respectability and authority with physical stiffness and lack of visible emotionality. It is a much more profound shift than it may seem at first sight, and it is undoubtedly going to strike some deep-rooted resistances. In this sense, communities that practice inner work are like laboratories for embodiment, places where we can experiment and get used to a new model of cohabitation where there is permission to shake, to dance, to make silly faces and to speak in tongues, where the barrier between mind and body is blurred, and we recognize each other as full humans who express themselves on physical, emotional, and mental levels alike.

Before concluding this quick review of embodiment practices, I feel it necessary to mention the delicate but important issue of sexuality. On one level, it is clear that if we want to bring awareness back into our whole body, we need to include our sexual organs. This may seem so obvious as to not be even worth mentioning, and yet, as an avid practitioner of Yoga, I can testify that most guided relaxations and embodied meditations routinely skip the genitals. Meditation teachers will unflinchingly guide their students into relaxing every part of the body, and when they come to the groin, they will skip the sexual organs altogether and instruct to relax the belly and the chest. This omission is all the more detrimental because, more often than not, the genitals hold significant amounts of contraction. So why are we not taught how to relax and energize them? One possible answer is the recognition of the deep-rooted mistrust of sexuality and the body that pervades our culture at least since St. Agustine (Baring, 2013, pp. 149-154). Today, acknowledging the reality of our embodied sexuality poses a challenge to many of our moral prejudices and unquestioned beliefs. Fortunately, embodied traditions like Hindu Tantra and Chinese Daoism, traditions that have a wealth of wisdom to offer on how to understand and cultivate sexual energy, are experiencing a burst of renewed popularity. While it is comforting to see that today, although timidly, the conversation on embodiment and sexuality is coming back into the inner work circles, none of the authors cited in this paper, with the exception of Hill (1960), makes any mention of sexuality.5

I recognize that a conversation on the role of sexuality in neuroscience and inner work requires more space than this paper can dedicate to it. And yet, my sense is that a frank study of sexuality is another area where neuroscience can contribute through its objective, impartial look. My conclusion from both study and direct experience is that there is no real possibility of creating a solid culture of embodiment without addressing, in one way or another, the issue of sexuality and its effects on our physical and psychic state.

Conclusion: Is It Good to Feel Good?

In approaching the end of this paper, I would like to reflect on the ethical dimension of neuroscience and its intersection with inner work. It is in the nature of both scientific exploration and deep introspection that they bring us to confront ethical and moral questions. But it is also common for us to ignore those questions, caught as we may be in the sense of power conferred on us by our new discoveries and the possibilities they open up. The human drive for knowledge is an unstoppable force, and it is inevitable that we continue to investigate the functioning of something as relevant to our lives as our brain and nervous system. That neuroscience has a rightful place amongst the most important endeavors of the human intellect is certain. But as we continue investigating the functioning of our brain, it is important to be aware of potential dangers that may be masked by the excitement of discovery.

I have already spoken into the temptation of reductionism: the risk of believing that we live in a simple world of which we fully understand the mechanics. But there is another factor to take into consideration: as we keep studying the brain, we are always one step ahead from wanting to intervene in its functioning. In fact, the enormous appeal of teachers like Robbins and Dispenza depends not so much on the information they provide, but on their claim that they can teach us how to change the way we think. Fundamentally, most modern neuroscience-inspired inner work frameworks are based on one ultimate promise: that, with sufficient training, we can choose our own thoughts and feelings. I believe that it behooves us to consider whether this objective is worthy and ethical.

It is true that, when we are trapped in our thought patterns, breaking through them may represent an unprecedented opportunity to change our lives for the better. But without denying the impact potential of changing our thought patterns, the possibility of deliberately hand-picking our thoughts and feelings may pose some difficult ethical dilemmas. If we can choose our thoughts, for instance, the question arises of what is the basis for choosing one thought over another. The unquestioned assumption of most authors is that we want to be happy and avoid suffering, an assumption that has all the weight of the Buddha’s teachings behind it.6 But is it always good to be happy? And if it were, once we all become masters at choosing our thoughts, why would anybody ever want to be sad? On some level, we all realize that the richness of life needs contrast, that we need an interplay of dark and light, joy and sadness, to express our full potential as humans. But our success-driven mentality, if translated to our inner life, may blind us to this basic truth about human reality.

We may be only a few steps away from being able to use technology to evoke or provoke specific thoughts and feelings. This is a possibility that would make us face scenarios we have never faced before. For example, imagine we were all carrying devices that could instantly put our brains in a positive state of mind of collaboration and synergy. What would mutual trust look like in such a context? Would you embark on a delicate enterprise with someone that looks reliable, cooperative, and cheerful, if you knew that they have a device in their pockets that reinforces those states of mind? What if the apparatus broke up? We have already outsourced to science and technology immensely relevant aspects of our lives. It is perhaps not too far-fetched to assume that the temptation to outsource our thoughts and feelings may be something to reckon with in the near future.

But there is more. The somewhat explicit promise of many successful teachers of inner work is that, by changing our thoughts, we can manifest not just happiness, but also material abundance and wealth. This connection between happiness and wealth is unheard of in Buddhism, whose basic teachings state that the accumulation of riches is one of the ways to fill our life with suffering. In this sense, contemporary teachers like Robbins and Dispenza are much closer to Hill, who, in the introduction to his bestseller, enticed the reader with “the secret that has made fortunes for hundreds of exceedingly wealthy men” (1960, p. xiii). But if we let the assumption that happiness is a sufficient condition for wealth go unquestioned, we may not see its logical consequence: that a poor person must by necessity be unhappy. Furthermore, although we may dream of a world where everybody is happy, it seems much less realistic to conceive of a society where everyone is wealthy in the sense that Robbins or Dispenza is.

In his study of the two brain hemispheres, McGilchrist (2019) offers a surprising counter-argument to the belief that it is always good to feel good. It turns out that the right hemisphere, the one that is embodied, connected to the world, responsible for our capacity to be empathic with others, also has a tendency to melancholy (p. 85). The left hemisphere, on the contrary, has a tendency to take a more optimistic view of the self and the future—a view that is often unwarranted (McGilchrist, 2019, p. 62). This connection between the capacity to experience sadness and a heightened capacity for empathy is in accordance with my own observation of human character. When we become too fixed in our pursuit of feeling good, we can lose the capacity to relate to our and other people’s suffering, thus maiming our empathy. A certain level of cosmic melancholy is, in my perception, a baseline that creates more empathy and openness than a stubborn optimism in the face of the inevitable suffering of life. Once again, these considerations are not intended to discount the value of practicing positive thinking and engaging in practices that foster optimism, but rather as a reminder of how important it is to find a dynamic balance between all opposites.

These are just some of the ethical and moral questions that neuroscience and inner work are presenting to us today. There will undoubtedly be more in the future. But the fact that neuroscience raises such questions in the first place is, in my view, something to celebrate. Given the possibility, I would always choose a “warm” study of the brain, one infused with ethical values and responsive to ethical questions, one that is in contact with deep inner work, philosophy, and even spirituality, over a purely scientific, “cold” version of neuroscience. I hope to have shown how neuroscience both benefits from and significantly contributes to inner work, to the fascinating endeavor of human consciousness discovering itself. My wish is that neuroscience and inner work can continue to inspire and challenge each other, supporting our ever-evolving quest into the mystery of who we are.

Figures

Notes

[1] Reductionism, in a nutshell, is the idea that phenomena can be explained by reducing them to their constituent elements. While reductionism can be useful in certain contexts (for example, disassembling a mechanical engine to understand how its parts work), it is less valuable when it comes to understanding complex phenomena such as human consciousness.

[2] Throughout this paper I will use the expression “inner work” to refer to any methodology that focuses on the contents of our inner experience with the purpose of promoting transformation and healing.

[3] This is, in McGilchrist’s own admission, a rather simplified way of describing the complex interactions between the two hemispheres.

[4] The unit of measurement does not matter as long as it is kept constant throughout the practice.

[5] Hill, in fact, saw it fit to dedicate an entire chapter to sexuality and its relevance for the manifestation of thoughts (1960, pp. 155-176).

[6] The “Four Noble Truths” are the first teaching the Buddha delivered to its disciples after having attained enlightenment. They illustrate the existence of suffering, its cause, its cessation, and the way leading to its cessation.

References

Rick Hanson’s homepage: https://rickhanson.com/

Baring, A. (2013). The dream of the cosmos: a quest for the soul. Dorset, England: Archive Publishing.

Dispenza, J. (2014). You are the placebo : making your mind matter. Carlsbad, California: Hay House, Inc.[Kindle Edition]

Hanson, R. (2009). Buddha’s brain : the practical neuroscience of happiness, love & wisdom. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications. [Kindle Edition]

Hill, N. (1960). Think and grow rich. Greenwich, Conn: Fawcett Publications.

McGilchrist, I. (2019). The Master and his emissary: the divided brain and the making of the western world. Yale University Press.

Robbins, A. (2007). Awaken the Giant Within. New York: Free Press. [Kindle Edition]

Shantideva (2008). The way of the Bodhisattva : a translation of the Bodhicharyāvatāra. Boston, Mass. Enfield: Shambhala Publishers Group UK distributor.